It looks like there is a growing push towards going back to distributing software as native binaries. However, it also looks that programmers these days seem to forget why we moved from native to bytecode binaries in the first place (maybe because the ones that still have that experience all migrated to management?). It’s not that native code doesn’t have any advantages, but far from it that it’s a silver bullet like we are (sometimes) led to believe.

First of all, let’s make one thing clear: there is no “execution” of bytecode of any sort. Simply because there is no CPU architecture that understands those instruction sets (not that it never existed, though). So, we are executing native code one way or another and the only difference is when we generate that native code: either immediately when creating an application package (so called ahead-of-time compilation or AOT) or when we run an application on target platform (called just-in-time compilation or JIT). And there are some really great benefits of producing native code at runtime.

One of those benefits, and most important for performance, are optimizations performed by the compiler. If you compile your application immediately to native code (AOT), compiler can only perform so-called static analysis of your source code like syntax validation, dead code removal, simple loop optimization and such. Those optimizations can greatly speed up generated code, but can go only so far, since the compiler at this stage knows very little about the target system that your code will run on (How many CPUs? Are they hyper-threaded or “full” cores? big.LITTLE? Do they support some advanced instruction set like SIMD? Is any specialized hardware available that we can use to offload work from the CPU?). At runtime, however, all that information is available and the compiler at that stage can generate much more efficient code, directly optimized for the exact system your code runs on (JIT). Additionally, runtime environments have the opportunity to perform so-called dynamic code analysis to determine exact ways in which your application is being used and to even further, while application is running, optimize its code to archive even better performances (most simple example of these types of optimizations is determining which functions are executed most often and then inlining them to eliminate overhead of performing a function call). Sure, you can tune your AOT compiler to target any specific hardware platform and even accomplish dynamic code analysis by leveraging profile-guided optimizations, but those techniques will tie your binary to that specific platform and optimize it for just one use case, which is far from optimal.

Described benefits of JIT over AOT stand independently of the programming language used. My tests below all use Java and OpenJDK/GraalVM runtimes and compilers, but I would be really surprised that very soon for example C++ or Rust code compiled to WebAssembly and executed on modern WASM runtime wouldn’t outperform native versions of those same executables. I said “very soon” simply because AOT compilers for those languages are currently more mature than available WASM runtimes, but it would be unrealistic to expect that WASM runtimes won’t evolve in the same way that JavaScript, Java or .NET runtimes did. However, note that I’m not trying to say that all bytecodes are made equal and that simply switching from AOT to JIT will make your Python code work as fast as equivalent C++ code. Bytecode is not magic, it’s simply an “intermediate” compilation target and as any such target, it greatly depends on source code from which it is being generated. So, if you take WASM bytecode generated from some very dynamic language like JavaScript or Python it would be false to expect that it would have same performances when JIT-compiled to native code as bytecode generated from languages like C++ or Rust (with Java, Kotlin, C# and Go standing somewhere in between those two extremes). Simply splitting compilation from AOT to JIT will improve performances for one specific code base, but it would be too much to expect from any compiler to compensate for implicit performance penalties any specific programming language brings in.

If I’m beginning to sound overly sympathetic for bytecode and JIT compilers, let me stop here for a moment and admit that it’s also true that if you need to compile your code during runtime it is inevitable that your application will take more time to start and probably have bigger peek memory requirements. So, if you value fast startup times, peak performance up from the start and as low memory requirements as possible (as is the case when building software for embedded systems, for example) then AOT compiling would probably be the way to go. On the other hand, if you are developing backend services that are expected to run for a long time, where you can tolerate some short “warm-up” period before achieving maximum performance, bytecode and JIT will be clear winners. In any case, there are no silver bullets here.

Note that I’m deliberately refusing to factor in effects of distributing a complete runtime together with your application code and effects it has on distribution size. In my opinion, distributing a runtime is a hack popularized by Docker, but I strongly believe that that hack is going away. We can see that Docker already has support for WebAssembly images and Kubernetes is gaining support for executing WebAssembly bytecode directly. I believe this approach will dominate in the future and size of native vs. bytecode binaries will stop being a differentiating factor.

Benchmarks

Although it would be interesting to test across different languages, compilers and runtimes,

I decided to stick to my own area of expertise and test three simple Java applications compiled to bytecode

using OpenJDK (packed with custom runtime produced using jlink) and to native binary using

GraalVM (omitting any PGO, since they are available only in

GraalVM Enterprise).

If any expert wants to contribute equivalent tests for other platforms, let me know.

Application(s) used for testing were deliberately simple: all they had to do is expose one REST endpoint for accepting an array of JSON objects and return exactly one of those objects in response. Exact logic is irrelevant, I used it just to give my service something to do. What is important is that all three applications implement exactly the same service with the only difference being the framework used to implement it: Spring Boot, Micronaut and Quarkus. I decided to test those frameworks specifically, because their authors are very vocal on advertising their support for native compilation (which is still not that common in the Java ecosystem).

I ran each test 5 times and used the best result. This allowed JIT to gather some runtime statistics and do its magic.

As would be expected, all source code is available in Github repo and you can find detailed instructions on how to run them below.

Also, note that I deliberately omitted memory tests. Although they would make sense if tests were implemented in language that manages its own memory, in garbage collected runtimes exact memory usage is hard to measure in a meaningful way. So I decided to run tests using memory configuration set on default values. Again, if anyone wants to contribute memory measurements, let me know.

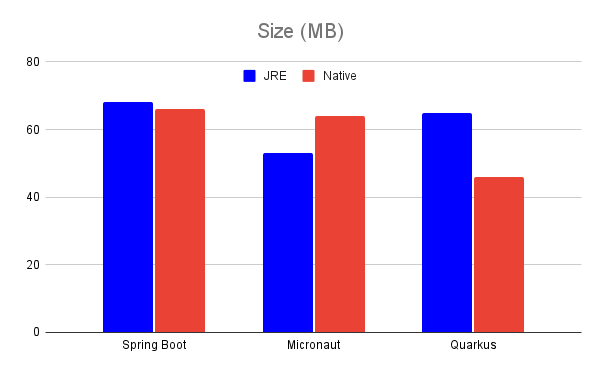

Distribution size

I’ll start with the least important results, at least in my opinion - size of generated distribution. Like I already said, distributing runtime with your application is a practice that will hopefully go away sooner or later, so size of our binaries will be once again determined solely by amount of our own code and dependencies used.

As we can see, there is no distinctive winner here.

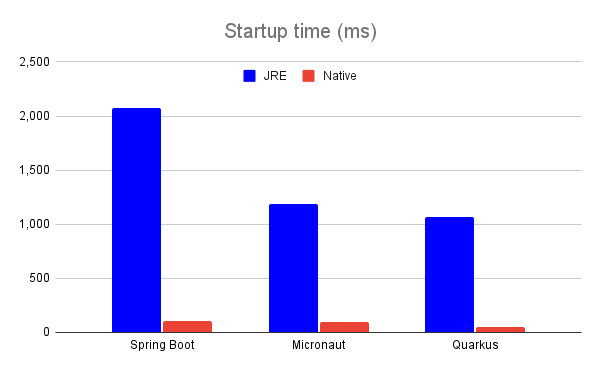

Startup time

I measured time that passed since issuing a command in terminal until application fully started by running:

date +"%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S.%N%:z"; <app-binary>

and subtracting the time of last log line from the time date printed.

Here we can see native code greatly outperforming bytecode. Truth to be told, this may have something to do with tested frameworks which are known to do a lot of runtime introspections during startup. When building a native image, those introspections are being performed at compile time, which improves startup time, but introduces some loss of functionalities, like authors of all three frameworks point out. I imagine these differences would end up smaller (but still present!) for Java applications that are built using some more lightweight frameworks/libraries and especially for applications written in some less dynamic languages like C++ or Rust.

However, these differences are to be expected and if startup time is your only concern, distributing your applications as native executables will give you clear benefits.

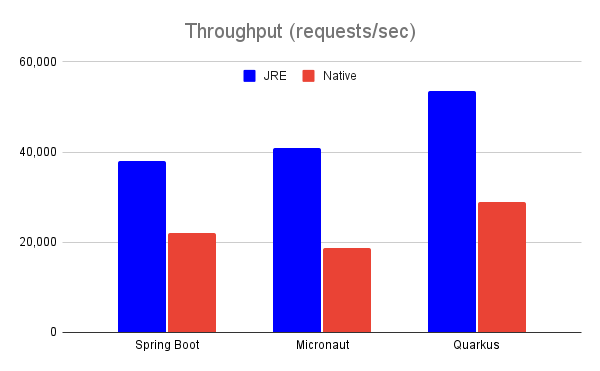

Throughput

Finally, the last test is how performant generated code is. I used wrk to test number of requests per second each application can serve by running:

wrk -t4 -c400 -d10s -s payload-10.lua <app-url>

Clear win for bytecode version of each application. Again, I assume that such great differences are at least partially caused by Java’s JIT infrastructure being way more mature than AOT one and I would expect for these differences to be at least somewhat smaller (but still present!) when tested with some other platforms and tools like C++/Rust native vs. C++/Rust WASM.

I’m not including all runs in these results (only best of 5 runs performed), but here you can experience one additional difference between native and bytecode versions: native versions had constant performance immediately from startup, while bytecode versions gradually improved their performances (as JIT compiler optimized code being executed) up to a point shown in the graph.

Conclusion

Although I tested only Java applications which have way more mature tooling for working with bytecode than native code, results are following expected behavior: native code is faster to start, but JIT-ed code has better performance. I expect the same to hold true in other ecosystems, at least when tools become mature enough. Also, I hope that it’s now more clear why everyone who’s marketing native code demos only startup time, not performance.

How I tested

Source code: https://github.com/gkresic/muddy-waters (note that that repository contains many subprojects, but only three are relevant to this article)

JDKs used:

- OpenJDK 17.0.5

- GraalVM 22.3.0

Frameworks tested:

- Spring Boot 3.0.1

- Micronaut 3.8.0

- Quarkus 2.15.1.Final

Spring Boot

URL: http://localhost:16003/eat

JRE

Build: ./gradlew :megalodon:runtime

Run: megalodon/build/image/bin/megalodon

Native

Build: ./gradlew :megalodon:nativeCompile

Run: megalodon/build/native/nativeCompile/megalodon

Micronaut

URL: http://localhost:16005/eat

JRE

Build: ./gradlew :sailfish:runtime

Run: sailfish/build/image/bin/sailfish

Native

Build: ./gradlew :sailfish:nativeCompile

Run: sailfish/build/native/nativeCompile/sailfish

Quarkus

URL: http://localhost:16004/eat

JRE

Build: ./gradlew :swordfish:clean :swordfish:build :swordfish:runtime

Run: swordfish/build/jre/bin/java -jar swordfish/build/quarkus-app/quarkus-run.jar

Native

Build: ./gradlew :swordfish:clean :swordfish:build -Dquarkus.package.type=native

Run: swordfish/build/swordfish-1.0.0-runner